Originally presented at the Good Medicine Confluence, Durango 2017 & published in the accompanying class essay book: http://planthealer.org/intro.html

Osha (Ligusticum porteri, L. grayii, and L. filicinum) is a beautiful, sacred, and highly useful plant in the Mountain West. Before getting into potential substitutes, I want to touch on issues around Osha sustainability. The utility of Osha is reflected in it’s popularity not only among herbalists but also among folks who might not otherwise use plants as medicine. Many folks here in Southwest Colorado take to the mountains to dig the root for themselves and their families.

A 3 year moratorium on Osha collection was enacted in 1999 due to growing demand and possible over-collection in the Western US (1). This covered parts of Washington, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Nevada and Wyoming. There are large populations here in the San Juan Range and in some other areas, but there isn’t much information on how robust Osha populations are throughout its range, or on the impact of human activities: Harvesting, logging, off road vehicle use, grazing, and land development.

There are stands in isolated and difficult-to-reach mountain terrain that offer protection for the species in the wild, and because of this not all herbalists are concerned about Osha populations. However, a worry is that heightened commercial interest may have an impact on easier accessed populations, as has happened with other valued North American plants. What happens when Dr. Oz decides that Osha is his favorite herb of the moment? These sorts of issues, along with the difficulty in cultivating Osha in large quantities, has led United Plant Savers has listed Osha as “At Risk” with respect to the potential for human impact on wild populations.

Research is being done in association with the the University of Kansas and the American Herbal Products Association Foundation for Education and Research on Botanicals (APHA-ERB, damn, that’s a mouthful) to assess Osha’s range and the ability of populations to recover after harvesting (2). It will take years for a solid understanding to emerge. What’s been learned so far is that Osha seems to propagate better in meadows compared to in the woods, at least in the sites studied. The meadow plants were larger and with bigger roots than those growing in the dapple shade of wooded plots (2). This has obvious applicability to both wild crafting as well as attempts to grow Osha. Also, there is some evidence that Osha may be capable of repopulating an area after harvest when given enough time (3, 4). In one example, areas that were harvested to varying levels (1/3, 2/3 or all of the plants in small plots) had filled back in after a few years, possibly regrowing from portions of the roots left in the soil after harvesting (3). In the other, replanting of Osha root crowns while wildcrafting appears to result in majority of these crowns “taking” after several years. Years being the key word in both examples. This is encouraging, but it also depends on whoever is harvesting Osha to do it in an ethical manner, leaving previously harvested areas alone for a long time.

In terms of harvesting Osha, leaving part of the root (well, technically, the rhizome) behind to regrow seems like a good option (3,5), or replanting the root crowns (4), as mentioned. Allowing the plants to go to seed before collecting the root is another. Taking it a step farther, ethnobotanist and biology professor Shawn Sigstedt encourages planting of the seeds while harvesting the root. Seeds are gathered once they are dry and brown and are planted upside down on a flattened “shelf” dug into a hillside. The seeds are closely spaced and covered by about an inch of loose soil and decaying leaves (Aspen would be good), then surrounded by twigs, branches or even small logs to prevent anyone, biped or quadruped, from stepping on the newly planted patches (6).

In terms of growing Osha, it can be cultivated at least to some extent. Along these lines, Elk Mountain Herbs partnered with the University of Wyoming for studies on growing Osha (7), and they now offer organically grown roots on their website, though it was out of stock when I looked to pick some up. Not the quickest growing crop… Another herb company, Shining Mountain Herbs, also report cultivating Osha, in a wooded area at 8500 feet. I couldn’t find any more details on their site, but look forward to hopefully being able to read more about their endeavor at some point. For the EMH/WU study, Osha was propagated from root crowns as well as from cold/damp-stratified seed (7). The best results came from planting at 8000 feet or higher either in Aspen groves or with the use of Aspen leaf mulch (something that’s not hard to come by here in Colorado). As with the U. Kansas/APHA-ERB preliminary results, more sun exposure was associated with bigger roots, at least in young plants, though the it was postulated that dapple shade may be better at lower altitudes (7). Roots were harvested after 4 years (7), so as with plants such as American Ginseng, Osha is a crop that takes a lot of time and patience to cultivate. The fact that it’s not as easily grown as, say, Oats, means that Osha may never become an herb with a vast supply chain of organically grown sources. But we can hope.

One last thought on Osha before moving on. Though the root is used for the medicine, a number of articles reference a book “Healing Herbs of the Rio Grande” (Curtin, L, 1947) with respect to using the stem for many of the same issues that the root is used for. I’ve not been able to access the book to check it out, but am guessing that if this pertained to the broad and powerful medicinal properties possessed by the root, we’d all be using the stems by now???

Another option, and the point of this whole thing, is to try substitutes, perhaps reserving Osha for those instances where you feel that nothing else will do. Osha is, of course, an excellent warming, anti-microbial, anti-spasmodic and immune stimulating herb that kicks pathogenic respiratory bugs in their proverbial asses while making the environment of our bodies less hospitable to their encroachment. This is only the tip of the Osha iceberg. But, for the purposes of this article, I’m focusing on respiratory support.

There are pretty solid alternatives that one can easily grow, buy or wildcraft to take some of the pressure off of the Osha stands lining our mountain trails. None of the plants are necessarily a perfect Osha substitute, but with some forethought and a little bit of mindful combining, you can do really well with conditions at which you’d normally throw Osha. I’ve summarized some of the more basic functions/uses in a table. The information comes from a variety of sources: My own training and small clinical practice, writings and talks by the herbalists who have been my go-to sources for continued learning, and the science literature. I don’t claim that the info here is complete, nor can I promise that you’ll agree with me! But, it’s a start.

Gumweed/Yerba del Buey (Grindelia squarrosa & other Grindelia spp)

I like calling it just plain old Grindelia. It’s a member of the Asteraceae that has a decent amount of overlap with Osha, functionally speaking. The common name is based on the sticky resiny substance that covers the flowers and buds, which can be chewed like gum (hence the name “Gumweed”). The taste might be off-putting to those used to mass quantities of sweetener in their chewing gum.

Grindelia is a warming, bitter, acrid and aromatic expectorant that, like Osha, has stimulating and relaxing properties. I was taught at one point to use Grindelia for wet coughs and Osha for dry. But the fact is that both plants will work for getting sticky, hardened phlegm, stimulating mucus secretion and liquifying the phlegm and both will also help clear boggy/wet, mucus-laden lungs. I remember one night especially, being awake at inappropriate hours with a nasty flu infection. I was drowning in sputum and wanted something to deal with the load o’ mucus while also chilling me out and helping me sleep. Grindelia came to the rescue, one by helping me to get the damned lungers out and, two, by making me really sleepy.

A side but related note. I may just be daft and missing the point, a very real possibility, but I’ve gotten myself wrapped up into a pretzel on more than one occasion on the whole stimulating versus relaxing expectorant thing. They are obviously valid and time tested categories. The thing is that the same herb may be called stimulating by one person and relaxing by another. But it seems like there are quite a few plants that are both. For instance, stimulating the liquification of mucus — thinning it and getting it out — while relaxing the airways at the same time. And perhaps even providing some moisture either in the form of a bit of mucilage, by irritating mucus membranes slightly to stimulate mucus secretion (stimulating mucus secretion and clearing mucus at the same time???…brain explodes).

Both Grindelia and Osha help with upper respiratory catarrh and will soothe a sore throat. For those nights when you wake up with a persistent, annoyingly sharp itch in the throat that no amount of coughing will ease, Grindelia is a great option. Both plants will also ease spasmodic coughs — bronchitis, emphysema, Whooping Cough, asthma (use in between attacks to reduce frequency and severity). At the same time, both will slow an elevated heart rate associated with “respiratory stress”. I find both to be pretty strongly sedating, although others may find Osha stimulating.

While the idea is to make the environment of our bodies not an inviting place for unwanted microbial residence, many of us will succumb to infection either due to burning the candle at too many ends, teaching a room full of kids with runny noses, boarding those flying petri dishes known as planes or having a bit too much wine. Accordingly, Grindelia has been used for respiratory issues, like Whooping Cough and Tuburculosis, that are bacterial in origin. Folks who are immunocompromised are susceptible to bacterial respiratory infections (and may contract some very weird bacteria), and bacteria may be the culprit in long-lasting respiratory infections that seem to not want to let go. Grindelia can be an antibacterial ally.

That said, the majority of respiratory infections are viral, at least initially. And while Grindelia is not usually cited specifically as an “antiviral” herb, it is helpful during colds and flu. I have used Grindelia by itself during the flu simply to experiment with it…it’s useful getting sick as an herbalist, educationally-speaking. Grindelia is commonly used in the Southwest right at the beginnings of a lung infection (8). Moreover, multiple components of Grindelia essential oil, including germacrene D, linomene, beta-caryophyllene, camphene, and alpha- and beta-pinene (9), have antiviral activity (10,11) and a few (limonene and the pinenes) are also immune stimulating (12). Whether these components are in high enough quantities in extracts to have anti-viral activity in the body, I don’t know, but I’ve had good luck with the plant. Regardless, if wanting an anti-viral boost, simply add in some Thyme, Garlic, Pine or, for something cooling if you don’t want the person to shrivel up and blow away, Elder.

Spring allergy season is in full swing here in Durango. Allergies are another issue for which both Grindelia and Osha provide support with their anti-histamine and snot-busting activities. Another way they help is through their bitter and aromatic principles that support digestive function. Good digestion means less mucus accumulation and reduced inflammation in general…both very helpful when allergy season arrives, and during the rest of the year as well.

Grindelia is native to the Americas, being found from Argentina to Canada and in most of the states here in the US. So, much more widely distributed than Osha. In fact, Grindelia squarrosa is listed as weedy and invasive by the USDA. Grindelia squarrosa var Nuda (aka. Grindelia nuda) is pretty common here in La Plata county, growing in disturbed sites and right smack in the middle of Durango. The latest batch I’ve tinctured was a “volunteer” patch growing along my friend’s walkway.

For a full list of our Western Grindelia species, see Michael Moore’s Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West (13) or visit www.SWSBM.com. His take on growing Grindelia: “…about the only reason for purposely growing this tacky weed would be for medicinal use. If you do so, throw the seeds out into the worst soil you can find and then disavow them when they sprout” (13). I really wish I got it together to meet and train with him before he passed, but am glad that there are so many of his herbal “children” and “grandchildren” around to learn from. Anyway, if you want to grow Grindelia, it seems to particularly like crappy alkaline soil.

Grindelia is fine used as a tea of leaf and flower, though I like to use it as a fairly high percentage alcohol tincture of the buds and flowers…the stickier, the better.

Damiana (Turnera diffusa, T. aphrodisiaca)

Next on the list of pungeant, warming respiratory- supporting plants is Damiana, a member of the Passifloraceae family. It’s astringent, bitter and drying. Many folks immediately think “aphrodisiac” when they hear “Damiana”. Others know it as a great mood enhancing and tension reducing herb. But it also has a long history of use as a respiratory herb in Central and South America where it and other Turnera species are used for influenza, bronchitis, expectoration, headache associated with too much coughing and for aches and

pains (14). Ellingsworth mentions it in his Materia Medica…”…soothing irritation of mucus membranes. This later property renders it valuable in treatment of respiratory disorders, especially those accompanied with profuse expectoration”. From King’s American Dispensary: “In respiratory disorders, it may be employed to relieve irritation and cough, and, by its tonic properties, to cheek hypersecretion from the broncho-pulmonic membranes. T It resembles more nearly the Grindelias, both in odor and taste.” It’s bitter components will support digestion, as yet another way to deal with mucus overload.

Damiana is aromatic, and a number of the compounds responsible for the distinctive aroma — 1,8- cineole, pinocarvone, limonene, alpha- and beta-pinene, thymol, p-cymene; caryophyllene and caryophyllene oxide (15) — are antiviral. Some of these are also immune stimulants, including pinene, limonene (12) and thymol (16). Damiana also contains the flavone, apigenin, which is active against a wide variety of viruses.

While Damiana’s antiviral and immune activating components may play a role in quashing initial respiratory infection, its antibacterial properties come to play in preventing or dealing with secondary lung infection with bacteria. Several of the the aromatic components mentioned above are antibacterial, as is arbutin, which is perhaps more famous as a component of Manzanita. In fact, Damiana’s essential oil is also active against drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (at least in a dish)(17)

It’s been coming in handy for me as a kids jiu jitsu instructor….Hands-on time with 20 or so 4-6 year olds, some of whom are regular nose-pickers, means that I feel the beginnings of a respiratory infection on a somewhat regular basis. (Yes, I know my immune system needs more work). In fact, as recently as last week, I grabbed the Damiana when I felt exceptionally fatigued, was starting to cough and had the chills with a bit of clamminess.

Damiana has been one of the herbs I’ll reach for during allergy season when I sometimes wake up in the morning with an irritating, mucusy cough and stuffy sinuses. A squirt or two has been sufficient to quell it. Stopping regular red wine intake might help me be better prepared for allergy season, but…..

Damiana is also used for asthma. It’s Mayan name is “mis kok” meaning “asthma broom”, and was used as such as a tea or by inhaling the smoke of the burned herb (18). In fact, smoking Damiana is my favorite way to use the herb for mood. A former student started me on this when a group of us were at TWHC in Mormon Lake. After passing around the pipe a couple of times, we were all laughing hysterically for about a half hour. Though this probably isn’t the best way to use it for lung support. For respiratory stuff, I use it in tincture form. Hmmmm…Chocolate Damiana Elixir for something other than getting it on?

Damiana as native to parts of the Southern US, Central and South America and the Caribbean. In warmer climates (USDA hardiness zones 9-11), it can be grown in fast-draining soil in the garden where they will get 4-6 hours of sunlight daily. For those living in colder climates, grow it in pots and bring it inside in the fall.

Elecampane (Inula helenium)

Elecampane, a Eurasian native and member of the Asteraceae, grows well in many parts of the US. It’s naturalized in the Eastern US and along the West Coast. In fact, it’s considered invasive in some states, so no guilt in harvesting it. It grows well at elevation here in SW Colorado and can reach towering heights. Well-drained, moist soil is best but Elecampane will tolerate a range of soil types. It will take full sun to part shade, though some shade is better in hot areas.

Elecampane continues the theme of warming, aromatic, acrid and bitter plants for respiratory support. It is a good stimulating expectorant for lungs full of phlegm, especially of the yellow/green variety. Though perhaps not the best for hot, dry conditions due to it’s warming energetics, Elecampane can stimulate mucus production and help liquify mucus to get it out in cases of coughs with hard, sticky mucus. It does contain a bit of mucilage to help sooth respiratory linings, though, it still may be good

to pair it with something cooling and moistening like Wild Mallow in these dry conditions. As with all of the plants discussed here, Elecampane both helps get the mucus out while at the same time relaxing persistent, annoying coughs.

Elecampane has noticeable calming effects as do Damiana, Grinedlia, and (at least for me!), Osha. This makes it useful for anxiety around the ability to breath when someone is in the throes of coughing fits (aside from the fact that it will help ease the coughing).

The antibacterial and immune activating activities of Elecampane may help with secondary respiratory infection. And while I usually think about it mainly as an expectorant and antibacterial herb, Elecampane does have antiviral constituents. These include phenolic acids like caffeic acid, dicaffeoylquinic acid and chlorogenic acid as well as terpenoids like camphor, thymol derivatives and farnesol (19, 20). As with Grindelia, I don’t know whether the levels of these are significant enough to have direct antiviral effects in the body.

This is yet another herb that will also help with allergies by relieving cough and congestion while supporting good digestive function. Moreover, Elecampane is, with regular low doses, a good lung tonic, strengthening lung function and aiding in chronic conditions like asthma, emphysema, COPD and long-standing bronchitis. Lung tonics are also handy here at 6500 feet where there isn’t quite as much oxygen as many of us are used to.

Angelica (Angelica archangelica, A. hendersonii, A. grayi, A. pinnata, others)

We have many Angelica species in the West, with some being more common than others. A. grayi and A. pinnata are here in the San Juan Mountains around Durango. Before harvesting Angelica, know your populations. Which species are near you? How plentiful are they?

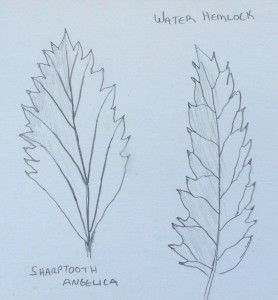

It has often been said that the Apiaceae family contains some of the most nutritious and medicinal plants along with the deadliest. When wildcrafting Angelica, a good way not to die is to know what its poisonous cousins look like. Those would be Water Hemlock (Cicuta douglasii) and Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum), in particular. The leaves are a good place to start in learning the differences. Poison Hemlock has fern-like leaves that more closely resemble those of Osha (!). Water Hemlock leaves more closely resemble Angelica. Check the leaves closely. Angelica’s leaflet veins go to the tips of the teeth along the margins, while Water Hemlock’s leaflet veins terminate in the cleft between the teeth. There are plenty of other ways to distinguish these plants as well, including seeds, leaf structure, etc.

A great option could simply be growing Angelica in a garden. Reminiscent of the conditions it treats, Angelica likes damp places. Strictly Medicinal Seeds carries

European Angelica (A. archangelica), Coast Angelica (A. hendersonii), Sharptooth Angelica (A. arguta) and other species. You could simply pick the one that works best in your area in terms of growing conditions.

So what does it do? You can probably guess by now. Angelica is great for respiratory issues with cold signs. It’s a blood-moving herb that will help dry up mucus later in infection, while also soothing the lungs with it’s essential oil. While Angelica is frequently used for cool conditions, Michael Moore also used it for irritability associated with hot illnesses (13). It’s antiviral and antibacterial properties make it appropriate for initial respiratory infection as well as for secondary infection. Though, to be honest, I’ve actually been having better luck lately using Grindelia or Damiana to stave off those early signs of infection. Don’t know if this is related to differences in herbal activities, or infecting agents, or due to the Angelica being a purchased tincture and the others being my own made with love!

Angelica can also stimulate mucus secretion and thin phlegm, so if using these properties to deal with the reluctant-to-come-up mucus that associated with dry, hot conditions, consider adding in a cooling and at least somewhat slimy plant like Mallow. Same, really, for any of the plants discussed in this article even if I neglected to mention this for each one.

The root, when fresh, may cause contact dermatitis or photosensitivity in some folks, so wear gloves when digging/processing fresh root. The seeds share some properties with the root, being acrid, aromatic and warming, bringing on a sweat and getting the immune system online, and they’re even easier to collect. I’ve not actually played with the seeds, though, other than picking one to chew when encountering Angelica in the mountains.

As with Osha, Damiana, and Grindelia, Angelica may also be supportive for arrhythmia associated with intense coughing spells, and for the anxiety that goes along with it. Angelica is also helpful for allergies, relieving some of the symptoms while also helping at a more foundational level by supporting good digestion and liver function like the other herbs here.

One of my favorite teachers grows Angelica archangelica in her garden. She had walked out into her garden around sunset and encountered her giant, stately Angelica backlit, and for a second thought it was an angel. How appropriate!

Thyme (Thymus vulgaris)

Yes, boring old garden Thyme. I probably use this more than any other plant when dealing with infections of the respiratory tract. Like many Mints, the essential oil of Thyme is strongly antiviral and antibacterial, as well as immune-stimulating. Like Osha and Angelica, the oil of Thyme is expelled from the body via the lungs, bringing the medicine right where it needs to be during a lung infection.

As is true for aromatic plants in general, the stronger smelling the Thyme, the more useful it will be. The Creeping Thyme I used to grow was pretty to look at but wimpy in the aroma department, while another, upright, variety along my south wall was supercharged. Not sure if the difference was in cultivar or due to the fact that the plant along the wall had a more stressful life getting baked in the sun all afternoon. Both, probably. I do know that having a lushly beautiful, very well-watered Thyme (or Sage, which is next on the list) will provide eye candy in the garden but won’t get you very good medicine.

I most frequently use Thyme tincture. Thyme is also great with lemon zest and juice together with a bit of honey, especially for laryngitis. And, the antiviral oil provided by lemon certainly can’t hurt. Thyme essential oil is good in a steam for sinus and lung issues. Many folks with chronic sinus issues may actually have a low grade fungal infection, which is why they continue to have issues even after throwing handfuls of antibiotics at the problem. Thyme has this covered. But the oil is strong and has the potential to irritate mucus membranes if used too frequently as a steam, so blend it or switch it up with other oils (eg. Bergamot, Peppermint, Lavender and the ubiquitous, and overused in my opinion, Tea Tree oil would be good).

As with the other plants here, Thyme will soothe spasmodic coughs of various etiology. And, with longer term use, may lessen the frequency and severity of asthma attacks.

Sage (Salvia officinalis)

Another Mint with its kick butt antiviral, antibacterial and immune boosting essential oil! If you don’t like the taste of Thyme, make Sage tea with lemon zest and juice and honey instead. Like the rest of the gang here, it will soothe spasmodic, annoying coughs and relieve lung and sinus congestion. Like Osha, Angelica, Grindelia and Elecampane, it is a weird combination of mostly drying but with some moistening as well. The moistening comes in part from it’s oiliness and the stimulation of mucus secretion, both of which can be used for a dry, unproductive cough, though perhaps combined with something cooling and soothing…Mallow, Mullein, Elder, etc.

Sage is also soothing to frazzled nerves, though it’s calming effects aren’t as strong to me as Grindelia or Osha. But it helps when one is cranky at catching a bug at an inconvenient time…like when deadlines are piling up.

Sage can be easily grown in many climate. It did fine in the garden I used to have while living at 8000 feet. It was unfazed by the cold winter and the intense summer sun. it even did fine in my garden when I lived at 8000’ feet….cold winters and intense sun in the summer. Either plugged into a garden bed or a pot is fine as long as the soil is well-drained. That said, it did fine in my heavy, amended clay soil.

And, finally, The Old Farmer’s Almanac says that having Sage planted in your garden means that you’ll do well in business….another reason to have this handy plant around.

So there you have it. There are other herbs that should probably be on this list. But this is it for now; my best stab at plants that can be used instead of always reaching for the Osha. Though they do have a lot of overlap, each plant here really does shine in it’s own particular ways. None are perfect substitutes for Osha but they do cover a lot of situations and can take some pressure off of our Osha populations.

References

1) Wilson, M. F. May 2007. Medicinal Plant Fact Sheet: Ligusticum porteri / Osha. collaboration of the IUCN Medicinal Plant Specialist Group, PCA-Medicinal Plant Working Group, and North American Pollinator Protection Campaign. Arlington, Virginia.

2) http://www.ahpafoundation.org/Osha.html & Kelly Kindscher, et al. (2013) Kansas Natural Heritage Inventory – Kansas Biological Survey.

3) http://www.herbsetc.com/content/PDF/Osha_root_sustainsabilty_.pdf

4) Hogan, P & J Fisher https://www.unitedplantsavers.org/images/pdf/2013-member-journal.pdf

5) Cech, R (2002) Growing at risk medicinal herbs, cultivation, conservation and ecology. Horizon Herbs LLC & United Plant Savers.

6) Phillips, N & M Phillips (2005) The Herbalist’s Way: The art & practice of healing with plant medicines. Chelsea Green Publishing Co, VT.

7) Panter, KL, et al (2004) Preliminary and Regional Reports – Preliminary studies on propagation of Osha. HortTechnology. 14(1):141-3. & https://www.elkmountainherbs.com/acatalog/Osha-Research.html

8) Moore, M (1990) Los Remedios: Traditional herbal remedies of the Southwest. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe.

9) Kaltenbach, J, et al (1991) Volitile constituents of the herbs of Grindelia robusta and Grindelia squarrosa. Planta Med. 57, Supplement Issue 2.

10) Erdogan Orhan, I, et al (2012) Antimicrobial and antiviral effects of essential oils from selected Umbelliferae and Labiatae plants and individual essential oil components. Turk J Biol. 36(2012):239-46.

11) Astani, A, et al (2010) Comparative study on the antiviral activity of selected monoterpenes derived from essential oils. Phytother Res. 24(5):673-9.

12) Li, Q, et al (2006) Phytoncides (wood essential oils) induce human natural killer cell activity. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 28(2):319-33.

13) Moore, M (2003) Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe.

14) Szewczyk, K & C Zidorn (2014) Ethnobotany, phytochemistry and bioactivity of genus Turnera (Passifloraceae) with a focus on Damiana – Turnera diffusa. J. Ethnopharm. 152(3).

15) Alcaraz-Melendez, L, et al (2004) Analysis of essential oils from wild and micropropagated plants of damiana (Turnera diffusa). Fitoterapia. 75:696–701.

16) Potentiation of macrophage activity by thymol through augmenting phagocytosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 18(2):340-6.

17) Bueno, J, et al (2011) Composition of three essential oils, and their mammalian cell toxicity and antimycobacterial activity against drug resistant-tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria strains. Nat Prod Commun. 6(11):1743-8.

18) http://www.entheology.org/edoto/anmviewer.asp?a=43

19) Kamkar, J (2001) Iranian J Med Aromatic Plants. 8:135-48. 20) Bourell, C, et al (1993) Chemical Analysis, Bacteriostatic and Fungistatic Properties of the Essential Oil of Elecampane (Inula helenium L.). J Essential Oil Res. 4:411-7.

~~~

Content © Dr. Anna Marija Helt, Osadha Natural Health, LLC. Permission to republish any of the articles or videos in full or in part online or in print must be granted by the author in writing.

The articles and videos on this website for educational purposes only & have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease or to substitute for advice from a licensed healthcare provider.